Climate Engineering

In short

Climate EngineeringTechEthos defines climate engineering as a technology family which enables the modification of natural processes [...] More represents a family of technologies – including primarily techniquesA technique is a procedure for realizing a goal [...] More for Carbon Dioxide Removal and for Solar Radiation Management – that could mitigate human-induced climate change. Some of the key ethical concerns surrounding these technologies include irreversibility, social inequality and transparency (for example, its imposition on some communities or countries that may not choose them) and responsibility towards future generations.

More about Climate Engineering

Climate Engineering represents a group of technologies that act on the Earth’s climate system to achieve a level of control over climate, thus holding the promise of mitigating climate change on a local and worldwide scale and detecting and responding to global threats due to the climate crisis. Also referred to as geoengineering, ‘Climate Engineering’ is a contentious term – you can read more about this in our glossary entry.

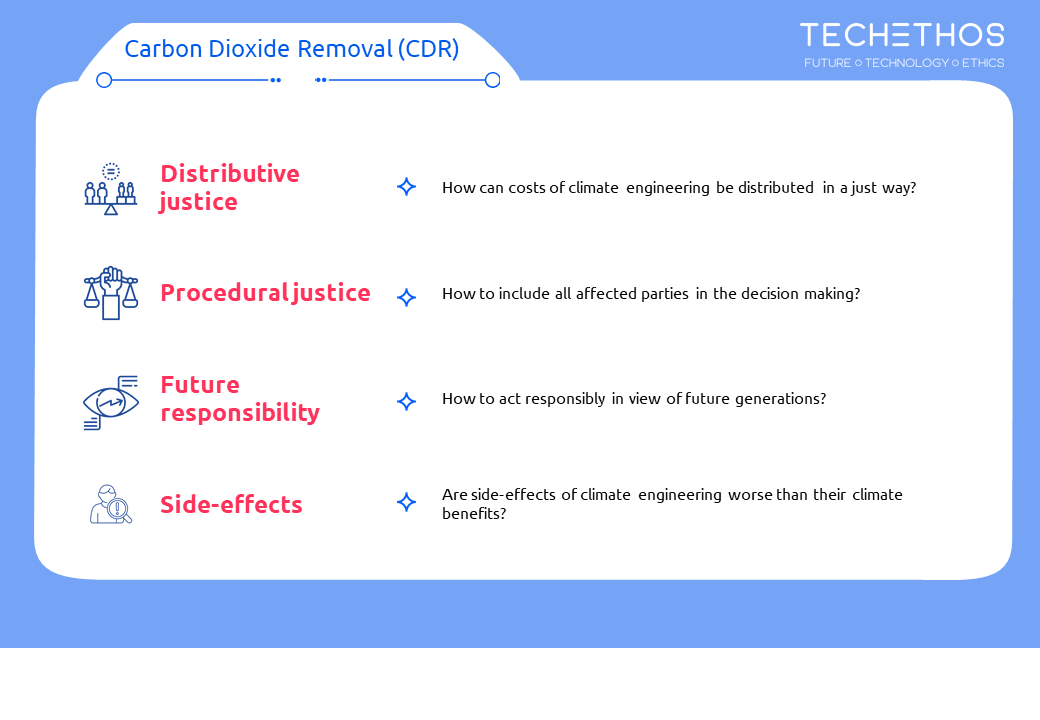

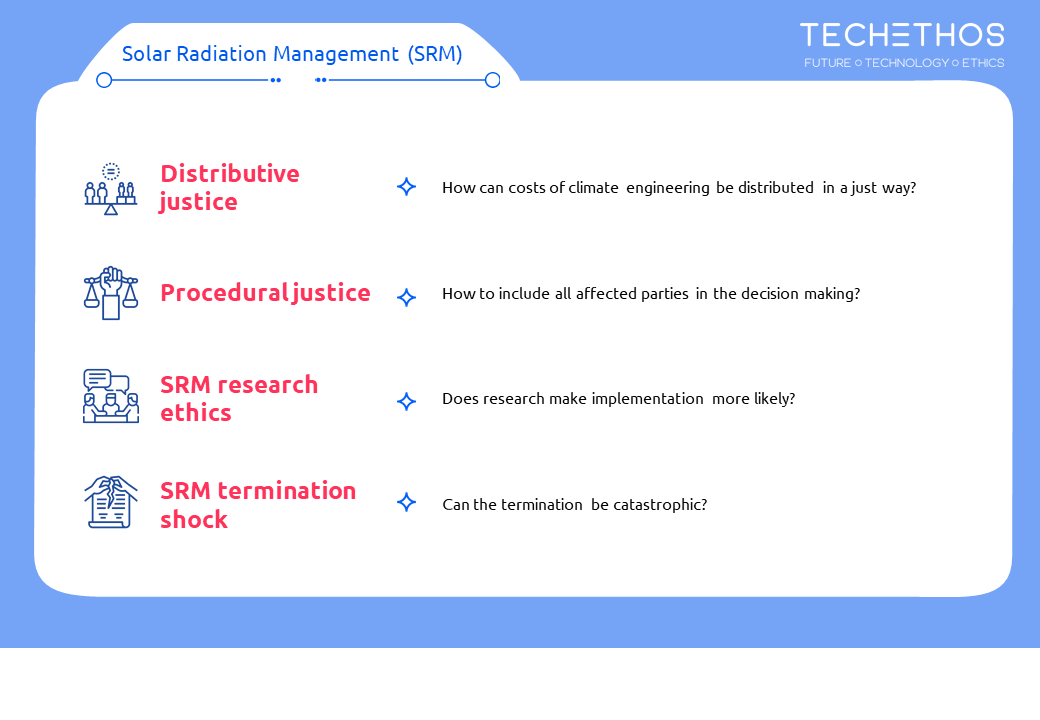

We distinguish between two main forms of Climate Engineering: Carbon Dioxide Removal (CDR), which removes atmospheric CO2 and store it in geological, terrestrial, or oceanic reservoirs, and Solar Radiation Management (SRM), which aims to reflect some sunlight and heat back into space. You can explore specific techniques that fall in these categories below.

Despite their high research and industrial relevance, ethical concerns arise around these technologies: who can access them? Will these technologies have an effect locally or globally, and who is going to decide about them? What could be the future environmental consequences of their applications?

-

CDR: Bioenergy with Carbon Capture and Storage

In this technique, biomass is used to generate bioenergy, and carbon capture and storage prevents emissions resulting from this process from reaching the atmosphere. -

CDR: Direct Air Capture with Carbon Capture and Storage

This technique combines chemical processes that capture CO2 from ambient air and underground storage. Storing CO2 in geological reservoirs or in mineral forms would remove CO2 for up to 1000 years. -

CDR: Enhanced Weathering

Rocks containing silicate and carbonate naturally absorb CO2, yet over very slow (geological) timescales. By spreading more of these particles onto soils, coasts and oceans, EW increases the total surface area of the planet that experiences this weathering effect, removing more atmospheric CO2. -

CDR: Afforestation and Reforestation

Afforestation refers to planting forests upon land where forests have not historically occurred, while Reforestation refers to restoring forests upon deforested land. -

SRM: Stratospheric Aerosol Interventions

This technique involves the injection of gas in the stratosphere, which converts into aerosols that block incoming solar radiation. -

SRM: Marine Cloud Brightening

By spraying sea salt or similar particles into marine clouds, this technique increases their reflectivity and blocks some incoming solar radiation. -

SRM: Ground-based Albedo Modification

This technique aims to increase the reflectivity of land surfaces, in order to deflect incoming solar radiation. Examples includes whitening roofs, land management practices, covering deserts or glaciers with reflective sheeting, and increasing the reflectivity of the ocean.

Ethical analysis

‘Ethics by design’ is at the core of TechEthos. It was necessary to identify the broad array of human and environmental values and principles at stake in Climate Engineering, to be able to include them from the very beginning of the process of research and development. Based on our ethical analysis, we will propose how to enhance or adjust existing ethical codesEthical codes indicate responsibilities o which individuals or organisations hold themselves to account [...] More, guidelines or frameworks.

Moral hazard: does climate engineering undermine climate mitigration?

This core dilemma asks if meaningful climate change mitigration is still possible if artificial changes are promised as solutions to the climate crises. This can take two distinct forms. Firstly, when mitigation is modelled over longer periods of time, the use of cheaper climate engineering later in the century might be preferred over more expensive mitigation costs at present or in the near future. Secondly, this choice of waiting until later to mitigate climate change can be particularly attractive at a political level, slowing down policy makers’ near-term efforts. Moreover, with some techniques that promise to mask the effects of climate change, mitigation risks to be abandoned altogether, despite not being sure empirically if CDR or SRM are possible at a large scale.

Moral corruption: Does climate engineering reflect a self-serving interest in avoiding politically difficult transitions away from fossil fuels?

This dilemma is closely related to that of moral hazard: the availability of climate engineering may be used as an argument by current generations to believe that they do not need to mitigate more rapidly now, thus passing the burden onto the next generation.

Hubris: Can climate engineering be justified by limited human foresightForesight is a systematic, participatory, future-intelligence-gathering and medium-to-long-term vision-building process [...]?

This dilemma emerges in context of the relationship between humanity and nature. Climate engineering seems to reflect an attitude of control or dominance over nature, to make it serve human beings. Researchers and ethicists consider that our current knowledge does not support some of the assumptions made about the possibility of achiving control over e.g., the global carbon cycle, while underestimating the harmful effects this could have.

In line with our key aim to enhance and adjust ethical guidance (in the form of codes, guidelines and frameworks) in the area of Climate Engineering, our team scanned the literature to identify already existing guidance that specifically addresses Climate Engineering or which is considered relevant in this area.

Existing ethical codes, if any, are largely considered insufficient and relatively unknown among private entities engaging in Climate Engineering research. The literature argues for the responsibility of researchers themselves but also that of funders regarding compliance with ethical codes. The inter-governmental Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) Code of Conduct for Responsible Fisheries is mentioned as a potential example upon which to develop a Climate Engineering code that is flexible enough to account for changing needs.

Researchers have called on the international community to engage in a dialogue regarding the social benefits and risks of Climate Engineering research given the lack of a generally-accepted ethical frameworkEthical frameworks outline general or specific principles [...] More. From their perspective, frameworks should be clearly defined and delimited and acknowledge the systemic impact of such technology families. The United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC), the Earth System Governance (ESG) Research Framework, and the Precautionary Decision-Making Framework (PDMF) are mentioned as potentially relevant in this endeavour.

Ethical guidelinesEthical guidelines collect general or specific principles [...] More for Climate Engineering per se are lacking, according to the literature, especially given the scale of intervention of such technologies. Some researchers are calling on the use of guidelines from the broader literature on ethics for research on human and animal subjects while such guidelines are being developed for Climate Engineering.

Legal analysis

There is no comprehensive or dedicated international or EU law governing Climate Engineering. However, many elements of this technology familyA technology family is a collection of technologies that share techniques that have common goals [...] are subject to existing laws and policies. Below, you can explore the legal frameworks and issues relevant to Climate Engineering and read about the next steps in our legal analysis.

Climate engineering has the potential to impact human rights in many ways, both positive and negative. There is a growing awareness that the impacts of climate change and environmental degradation are devastating for the enjoyment of human rights (e.g., the right to life, food security, health) for people today and in future generations. Therefore, the use of climate engineering to mitigate harms associated with climate change could enhance enjoyment of human rights. On the other hand, manipulating Earth’s climate through climate engineering may cause unforeseen and uncontrollable consequences that would further threaten human rights.

States have an obligation under human rights law to ensure that climate engineering activities respect and promote human rights. Furthermore, the Paris Agreement recognised that the actions to address climate change, which may include climate engineering, must be guided by human rights.

TechEthos has looked at three clusters of rights that encompass the main issues related to human rights and climate engineering: human rights pertaining to scientific research, procedural human rights, and substantive human rights.

Under international law, States could be held liable for harm caused to another State from a climate engineering activity.

TechEthos has looked in detail at applicable international and EU laws and policies, and in particular at the prohibition of transboundary environmental harm, or the ‘no-harm rule’. This ensures that activities within a state’s jurisdiction and control respect the environment of other states.

Climate engineering has the potential to impact environmental law in many ways, both positive and negative. The use of climate engineering technologies to mitigate harms associated with climate change could enhance the protection of the environment. On the other hand, however, manipulating Earth’s climate through climate engineering may redistribute environmental risks and cause unforeseen consequences to the environment and human health.

States have an obligation under international environmental law to ensure to protect the environment and human health when deploying climate engineering activities and to take steps to prevent transboundary environmental harm as much as possible.

TechEthos has looked in detail at the main environmental law regimes applicable to climate engineering technologies: environmental impact assessments; corporate disclosure; public participation; sustainable development; pollution prevention; environmental management of waste and chemicals; and environmental protection and liability for harm.

Climate engineering activities may help States meet their climate obligations within climate law regimes. While not required, some specific types of climate engineering activities, such as Carbon Capture and Storage, Carbon Capture and Usage, and nature-based solutions, are explicitly referenced in law as potential options available to States.

TechEthos has looked in detail at international and EU law and policies, emission reduction goals, carbon emissions trading and geological storage of CO2.

Some proposals for solar climate engineering would involve activities in outer space.

As international space law predates climate engineering, there is no international space treaty dedicated to climate engineering, nor do any existing space law treaties explicitly refer to climate technologies. However, it is likely that specific aspects of space-based climate engineering activities would be governed by existing international space law treaties, and States’ responsibilities in outer space law would likely extend to climate engineering activities, though the extent and specifics of those obligations are unclear.

TechEthos has considered specifically the relevance of international and EU laws and policies, state responsibilities in outerspace, environmental protection and liability from environmental harm in space, and the exploitation and mining of space resources.

Some proposals for climate engineering would involve activities in the marine environment or result in impacts to the marine environment; examples include ocean fertilisation, enhanced kelp farming, and marine cloud brightening.

While there is no comprehensive law of the seas treaty addressing climate engineering, associated activities that impact marine environments would be governed by existing international and EU law. Furthermore, there are dedicated – though non-binding – rules on ocean fertilisation and transboundary seabed CO2 storage, which were developed in response to concerns about proposed climate engineering projects.

TechEthos has looked explicitly at EU and international laws and policies, and the following legal issues: states’ obligations: assessment, permitting and monitoring; marine pollution and dumping; the non-binding international ban on ocean iron fertilisation; and deep seabed drilling and carbon storage.

In addition to analyzing the obligations of States under international law and/or the European Union, the project conducted a comparative analysis of the national legislation of three countries: Australia, Austria, and the United Kingdom.

The three case studiesA case study is a research approach that is used to generate an in-depth [...] More specifically examined the current status of climate engineering, ongoing legal and policy developments, human rights law, environmental law, and climate change law.

We complemented this analysis with a further exploration of overarching and technology-specific regulatory challenges. We also presented options for enhancing legal frameworks for the governance of climate engineering at the international and national level.

Societal analysis

This type of analysis is helping us bring on board the concerns of different groups of actors and look at technologies from different perspectives.

TechEthos asked researchers, innovators, as well as technology, ethical, legal and economic experts, to consider several future scenarios for our selected technologies and provide their feedback regarding attitudes, proposals and solutions.

Read the policy noteFrom June 2022 until January 2023, the six TechEthos science engagementPublic engagement describes the myriad of ways in which the activity and benefits of higher education and research can be shared with the public [...] organisations conducted a total of 15 science cafés involving 449 participants. These science cafes were conducted in: Vienna (Austria), Liberec (Czech Republic), Bucharest (Romania), Belgrade (Serbia), Granada (Spain), and Stockholm (Sweden).

Science Cafés had a two-fold objective: build knowledge (e.g., ethics, technological applications, etc.) about the selected families of technologies: climate engineering, neurotechnologies and digital extended reality as well as recruit participants for multi-stakeholder events.

Seven out of 15 science cafés were dedicated to the Climate Engineering technology family and addressed topics ranging from climate change and energy sources to technologies like carbon capture and storage (CSS), bio energy carbon capture and storage (bio-CCS) and solar radiation management (SRM).

Discover TechEthos ‘science café’ series in our news article:

An important perspective the TechEthos project wanted to highlight alongside expert opinions was the citizen perspective. To encourage participation and facilitate conversation, an interactive game (TechEthos game: Ages of Technology Impact) was developed to discuss the ethical issues related to climate engineering, digital extended reality (XR), neurotechnologies (NT), and natural language processing (NLP). The goal of this exercise was to understand citizens awareness and attitudes towards these emerging technologiesTechnologies whose development and application are not completely realised or finished, and whose potential lies in the future. [...] to provide insight into what the general public finds important.

The six TechEthos science engagement organisations conducted a total of 20 scenario game workshops engaging a wide audience from varied backgrounds.

From the workshop comments the citizen value categories were extracted through qualitative coding, allowing for comparisons across all workshops. Each technology family exhibits distinct prominent values.

CE highlights ecosystem health, followed by safety, reliability, effectiveness, efficiency, and justice, given its focus on manipulating natural systems. Safety and reliability are important across all three families. Responsible use and accountability are vital in NT, NLP, and XR. Ecosystem health is a shared concern across all families.

Media discourse on technologies both reflects and shapes public perceptions. As such, it is a powerful indicator of societal awareness and acceptance of these technologies. TechEthos carried out an analysis of the news stories published in 2020 and 2021 on our three technology families in 13 EU and non-EU countries (Austria, Czech Republic, France, Germany, Ireland, Italy, Netherlands, Romania, Serbia, Spain, Sweden, UK, and USA). This used state-of-the-art computational tools to collect, clean and analyse the data.

For climate engineering, the media discussion on technologies to tackle issues of climate change is heavily dominated by green hydrogen. This is a technology aimed at tacking climate change, but which does not strictly fall within the climate engineering family of technologies as defined by TechEthos, an aspect that TechEthos has to remain aware of.

Furthermore, we could observe that solar engineering techniques are rather rarely discussed in new stories collected for this family of technologies. Technologies such as solar radiation management or cloud modification or whitening appeared rarely in the media scanned, while afforestation, reforestation, carbon capture, sequestration and storage are among the most discussed topics. Hence, the media discourse as captured by this study indicates there might be less public awareness of solar radiation techniques, compared to other climate engineering techniques such as afforestation or carbon capture, usage, and storage techniques.

Read the reportOur Recommendations

Explore the project recommendations to enhance the EU legal framework and the ethical governance of this technology family.

This policy brief sets out recommendations based on the regulatory challenges related to CDR that were identified in our analysis of EU laws and policies. We address them to EU policymakers and officials involved in the preparation of legislative or policy initiatives related to climate action, climate technologies, climate engineering, geoengineering, carbon removal, and CDR specifically.

This policy brief sets out recommendations based on the regulatory challenges related to SRM that were identified in our analysis of EU laws and policies. We address them to EU policymakers and officials involved in the preparation of legislative or policy initiatives related to climate action, climate technologies, climate engineering, geoengineering, and SRM specifically.

This policy brief explores the regulatory challenges within EU laws and policies surrounding CDR. Addressed to European Union (EU) policymakers and officials engaged in climate-related initiatives, the recommendations are crafted to ensure ethical, rights-based, and sustainable development of CDR.

This policy brief emphasizes ethical governance, international collaboration, and public engagement to ensure responsible, just and sustainable SRM research.